Evaluation of the Saskatoon Mental Health Strategy (MHS) Court: Outcome and Cost Analysis

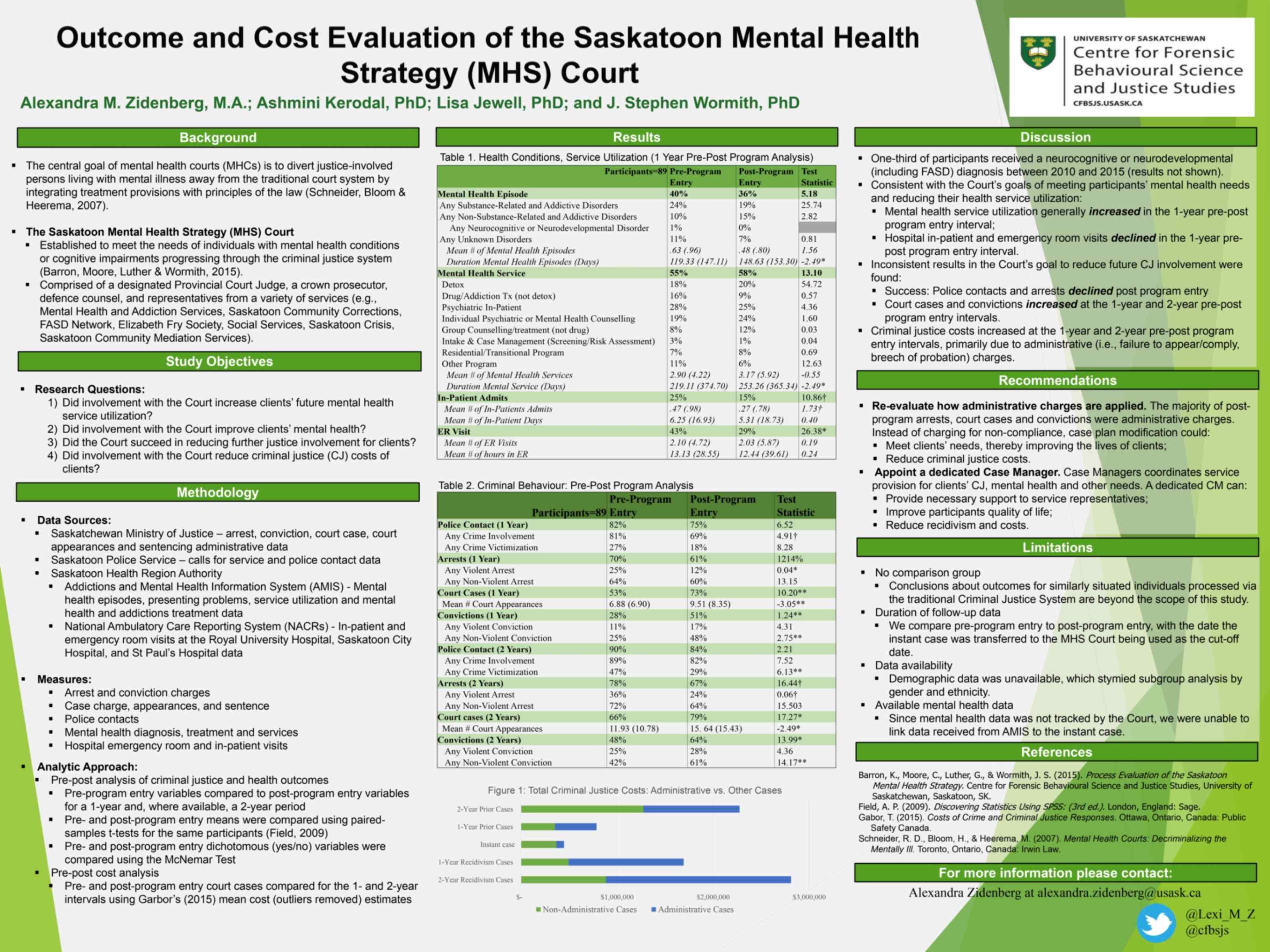

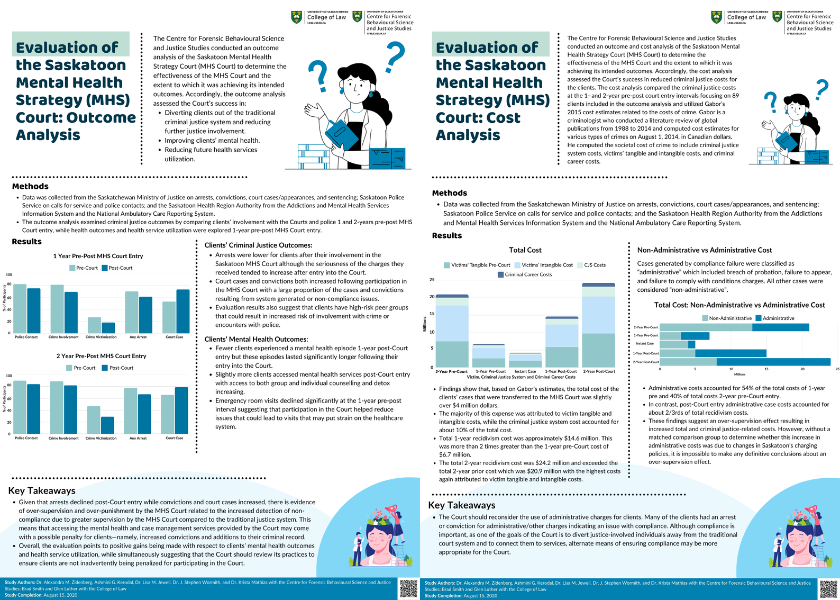

The purpose of the current evaluation is to provide the Steering Committee of the Saskatoon MHS Court with an outcome and cost evaluation detailing the outcomes of the MHS Court’s first-year cohort of defendants.

By Alexandra M. Zidenberg, Ashmini G. Kerodal, Lisa M. Jewell, Krista Mathias, Brad Smith, Glen Luther, and J. Stephen WormithBringing together a multidisciplinary team of community stakeholders and legal professionals, the Saskatoon Mental Health Strategy (MHS) Court, hereafter the MHS Court, aims to assist justice-involved individuals living with mental illness and cognitive impairments (Barron et al., 2015). To determine the effectiveness of the MHS Court and the extent to which it is achieving its intended outcomes, the Centre for Forensic Behavioural Science and Justice Studies (CFBSJS) was invited to conduct a multi-phase evaluation of the Court.

This evaluation was guided by the following questions:

- Did the MHS Court succeed in diverting clients out of the traditional criminal justice system?

- Did the MHS Court succeed in reducing further justice involvement for clients?

- Did involvement with the MHS Court improve clients’ mental health?

- Did involvement with the MHS Court reduce clients’ future health service utilization?

- Did involvement with the MHS Court reduce criminal justice costs of clients?

MHS Court Clients’ Profile

Participants

Ninety-two defendants participated in the MHS Court in the first-year cohort, that is, were transferred into the MHS Court between November 18, 2013 and November 17, 2014. Data was available for 89 clients adjudicated through the MHS Court.

Instant Case Arrest Charge, Conviction, and Sentence

Over half of the cases transferred to the MHS Court were for non-violent arrests (57%) followed by violent (40%) and traffic (2%) arrest charges. Almost three-quarters of clients (74%) received a conviction on their MHS case. The most common index conviction charge was for non-violent offences (46%), while just over one quarter (26%) of clients were convicted of a violent crime. The most common sentence for the instant case was probation (47%) followed by suspended sentences (25%), jail sentences (19%), fines (12%), and conditional sentences (10%).

Conclusion

This pre-post outcome and cost evaluation found several strengths of the MHS Court. Fewer clients had police contacts, were victims of crimes, or arrested in the 2-years following their MHS Court entry. Clients were able to access several mental health services and treatments postCourt entry, while their hospitalizations and emergency room utilizations declined in the 1-year post-Court entry period. The pre-post arrest analysis was also promising, as reductions were observed in any violent and non-violent arrests. However, the crime severity weight of all arrests increased in the pre-post arrest outcome analysis, indicating some caution is required in interpreting these data. Clients’ court cases did increase subsequent to their MHS Court entry, but this increase declined in the second year post-Court, indicating a possible supervision effect during the MHS Court case. Inclusion of data categorizing arrests, cases, and convictions by seriousness (i.e., summary, indictable or hybrid), and a matched comparison group are required to make any definitive conclusions about any recidivism and/or the over-supervision effects.

The absence of program data, including any indicators of successful MHS Court completion, was a challenge. As a result, we used recidivism, mental health, and health utilization as our outcome measures and no analysis on completers (clients who successfully completed the MHS program) vs. non-completers was possible. Future evaluations would benefit from the inclusion of program data and a matched comparison group, demographic data, and a longer follow-up period. Further, due to the small sample size, comparisons on the effects of co-occurring (i.e., substance abuse with mental disorder) and different mental health conditions on recidivism was not feasible.

Despite these limitations, we hope that the findings and the following recommendations are useful to the Steering Committee of the Saskatoon Mental Health Strategy. Our hope is that our report will generate discussions within the Steering Committee about the purpose, direction, and outcomes of the MHS Court, and perhaps support efforts to secure funding for dedicated staff and data tracking of clients’ programming and outcomes.