Modifying the Community Screening Instrument for Dementia (CSI’D’) for an Institutional Setting

Canada is facing a rapidly aging incarcerated population similar to other nations. A validated, reasonably accurate, dementia screen would assist prison staff in identifying older offenders in need of a clinical dementia assessment. To address this need, in 2019, the University of Saskatchewan’s Centre for Forensic Behavioural Science and Justice Studies (CFBSJS) initiated a three-phase study to identify and validate one or more culturally appropriate dementia screening tools for the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC).

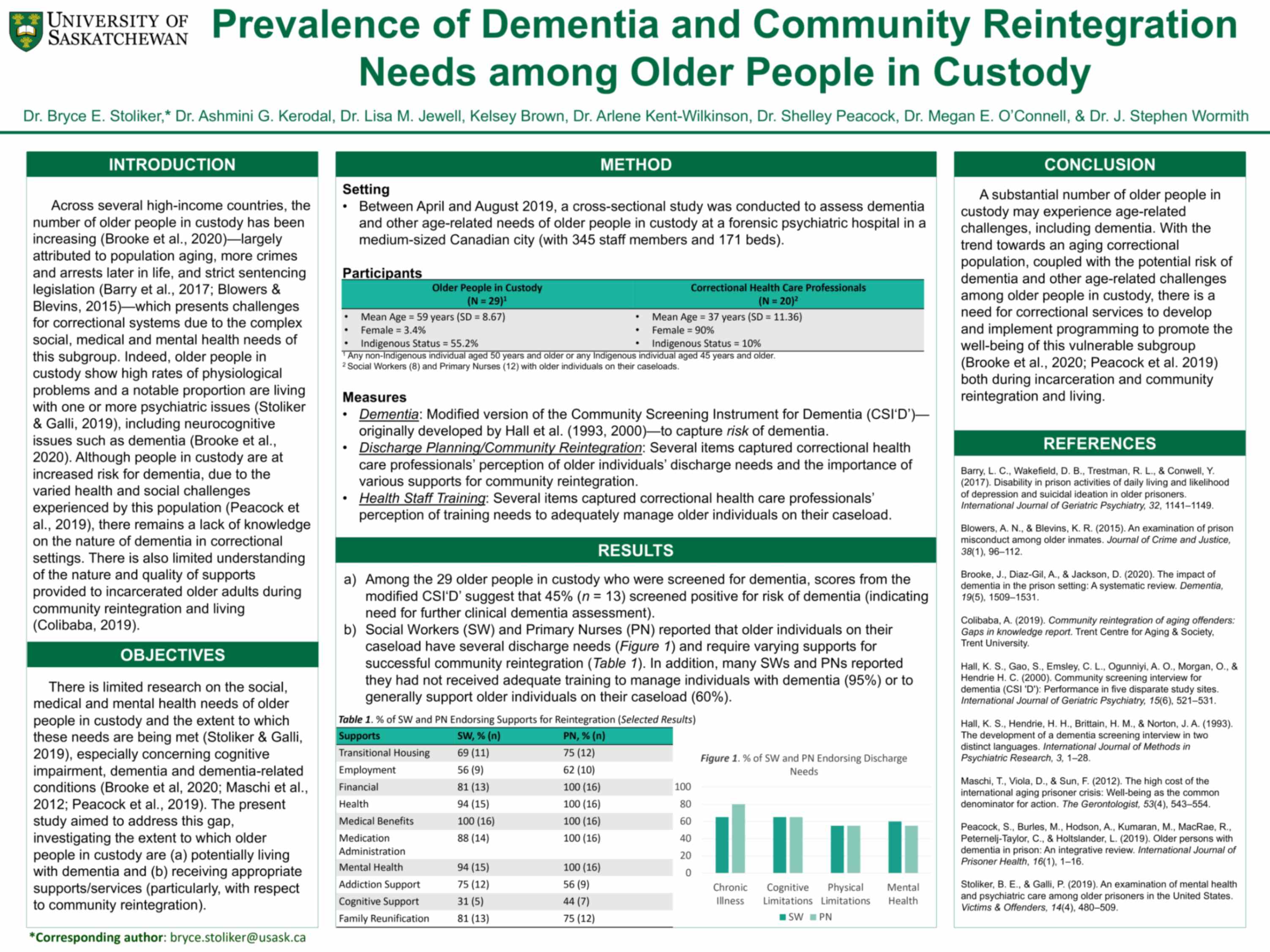

By Ashmini G. Kerodal, Lisa M. Jewell, Arlene Kent-Wilkinson, Shelley Peacock and J. Stephen WormithThe current report presents the findings from Phase 1 of the Dementia Project. In this phase, a culturally appropriate dementia screening tool, the Community Screening Instrument for Dementia (CSI‘D’), was modified and administered to older offenders in the Regional Psychiatric Centre (RPC), a CSC Regional Treatment Centre located in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. In addition, a staff survey was conducted to determine the perceived health needs of older inmates and the extent to which RPC accommodated these health needs in the facility and in discharge planning. The results from this component of the study are presented in a companion article (Stoliker et al., in progress). For the purpose of the Dementia Project, an “older offender” was defined as a non-Indigenous inmate aged 50 years and above, and an Indigenous inmate aged 45 years and above.

In Phase Two, a clinical dementia diagnosis of the older offenders administered the CSI‘D’ screen in Phase One will be conducted via a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA). In addition, a second promising dementia screen, the Canadian Indigenous Cognitive Assessment (CICA), will be administered. In Phase Three, the CSI‘D’ and CICA screens and a clinical dementia diagnostic assessment will be completed with older offenders in a nationally representative sample of CSC prisons to validate one or both screens for a prison setting. In all phases, while the screens are being validated, health and accommodation recommendations will be provided to older offender participants.

Methods

A multi-method strategy—including data from CSC’s Offender Management System (OMS), interviews with older offender participants and self-administered surveys to the older offenders’ Primary Nurses—was used to determine the rates of older offenders at RPC who should be referred for clinical dementia assessment.

Participants

Fifty-five older offenders were identified as initially meeting the eligibility criteria for the study. Of these individuals, 53% consented (n = 29) to participate, 27% (n = 15) declined participation, and 11 were deemed ineligible due to being in the regional hospital (n = 1, 2%), being deemed dangerous (n = 1, 2%), 4%), not having the capacity to consent (n = 1, 2%), or being discharged/transferred to another CSC facility (n = 7, 13%).

Conclusion

Almost half of the inmate sample (45%) was flagged for a clinical dementia assessment. This is slightly higher than the upper limit of the range obtained from a prior meta-analysis of dementia studies conducted on American prison samples (1% - 44%; Maschi et al., 2012). However, it should be noted the dementia estimate among older inmates in the RPC is likely to be overestimated due to the following reasons: a) health screens tend to be over-inclusive to ensure persons in need receive health services (Trevethan, 2017); b) Informant Scores were unavailable for 28% of the sample, and the D.S. is a more accurate dementia flag compared to the Cog. Score only (Hall et al., 2000); and c) almost half of older inmates were deemed ineligible (20%) or declined to participate due to having “no issues or problems with memory/ dementia” (27%). Assuming a lower limit whereby no excluded older offenders required a dementia assessment and an upper limit whereby all excluded older offenders required a dementia assessment, the possible rate of older offenders at RPC who may require a dementia assessment may range from 24% to 71%.

In reviewing these studies findings, several limitations should be kept in mind. Notably, accuracy results were not produced for the modified CSI‘D’ because the outcome variable, dementia diagnosis, will not be available until Phase 2. In addition, the low response rate for both older offenders and PNs adversely affected the reliability of the results. Finally, RPC is one of five Regional Treatment Centres (RTCs), which house CSC inmates with high mental health needs. Results from RPC are not generalizable to other CSC facilities due to the higher rates of older inmates and inmates with high mental health needs at RPC. The higher rate of Indigenous inmates in RPC compared to other RTCs also makes generalizations to other RTCs problematic. Even with these limitations, this study is an important first step in producing a validated dementia screen for institutional populations and is necessary to formulating a cost-effective strategy to identify and provide health care to CSC older offenders with dementia.